Location

Queensland, Northern Territory, Western Australia

What it is?

Cane toads are native to South and mainland Central America where they’re also known as ‘marine toad’ and ‘giant’ toad. Since their introduction to Australia in 1935, they’ve continued to cause local extinctions of native animals, and they’re marching their way across the country. They were brought to Australia from Hawaii with the intention of controlling the destructive cane beetle in sugar cane fields in North Queensland.

Only 102 cane toads were brought over to be bred (an indication of their breeding potential – 2,400 toads were released). It seemed like a great idea at first, however, the cane beetles and the cane toads rarely crossed paths. Cane beetles live high on the upper stalks of the cane plant, and cane toads can’t jump that far so they barely had any impact!

In less than 85 years, the cane toad population has multiplied to epidemic proportions. Now, some scientists estimate that there are more than 200 million cane toads hopping around our continent, wreaking havoc on our ecosystem and expanding across northern Australia at a rate of 50km every year (CTC, 2019).

Cane toad are highly adaptable. Their habitat ranges from rainforests, coastal mangroves, sand dunes, shrubs and woodlands. They don’t need much water to reproduce. They can also survive temperatures between 5°C – 40°C, so don’t be surprised to find them adapting to survive the cold winters down south (CTC, 2019).

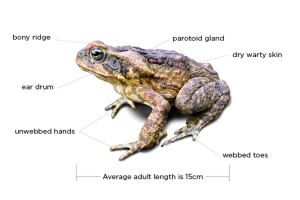

Cane toads have a number of distinguishing features, including:

- dry, warty skin that may be grey, yellowish, olive-brown or reddish-brown

- a bony ridge from their eyes to their nose

- leathery webbing between their back toes

- no webbing between their front toes

- large glands on each shoulder.

Food

Cane toads are ground-dwelling predators that forage at night in a wide variety of habitats. They primarily eat snails, terrestrial and aquatic insects and will even eat food left out for pets (DCCEEW, 2023).

Cane toads will eat anything they swallow – both dead and living. This includes pet food, carrion and household scraps, but mostly they exist on a diet of living insects (CTC, 2019).

Reproduction

Cane toads need constant access to moisture to survive, but instead of drinking water, they absorb it through the skin on their belly. If forced to stay in flooded conditions, cane toads can absorb too much water and die, alternatively they can also die from water loss during dry conditions. Being an introduced species to Australia there are no specific predators or diseases that can control the cane toad.

They can breed at any time of the year but prefer the start of the wet season. The female can lay between 8,000 and 30,000 eggs at a time and will do so in slow moving or stagnant water. The babies can reach adult size within one year (DCCEEW, 2023).

Male toads start calling for mates after the first summer storm, and they congregate after dark in shallow water where they wait to mount females. Once fertilised, female cane toads lay anywhere between 8,000 to 30,000 eggs – twice a year! These eggs hatch within 1-3 days and tiny tadpoles emerge (CTC, 2019).

These tadpoles are less than 3.5cm long, and they’ll stay in this phase up to 20 weeks, depending on their food supply. Adult cane toads can live between 5-10 years in the wild (CTC, 2019).

Defence Mechanisms

The cane toad defends itself through poison. Adult cane toads produce toxin from glands over their upper surface, but particularly from the bulging glands on their shoulders. The venom is exuded when the toad is provoked. While some birds and native predators have learned to avoid the poisonous glands, other predators are more vulnerable and die rapidly after ingesting the toxin. The toxin acts on the heart and the central nervous system and can be absorbed through bodily tissue such as the eyes, mouth and nose (DCCEEW, 2023).

Cane toads are toxic at all life stages – from eggs to adults. They have large swellings called parotoid glands on each shoulder behind their eardrums This is where they carry their milky-white toxin (known as bufotoxin). Their skin and other glands across their backs are also toxic (CTC, 2019).

This spells bad news for Australia’s native species, as they haven’t had time to adapt to these toad toxins. One lick or bite can cause native animals to experience rapid heartbeats, excessive salivation, convulsions, paralysis and death (CTC, 2019).

Local Indigenous rangers tell stories of birds that fall dead from the sky after eating a tasty cane toad (CTC, 2019).

Control Measures

It is possible to control cane toad numbers humanely in small areas, such as a local creek or pond. This can be done by collecting the long jelly-like strings of cane toad eggs (see photos) from the water or by humanely disposing of adult cane toads(placing them in the fridge overnight, then moving to the freezer the next day). Control is best at the egg or adult stages because cane toad tadpoles can easily be confused with some native tadpoles (DCCEEW, 2023).

ToadScan is a national website developed by the New South Wales Department of Primary Industries to help communities, local governments and pest controllers gather data on cane toads in order to support control programs.

On the website you can report sightings of cane toads, the damage cane toads are causing and control activities happening in your area.

Interactions with other species

While we can’t stop the cane toad invasion in the Kimberley, we can help native species survive it. In partnership with the Cane Toad Coalition, WWF-Australia is working to train native predators (like the yellow-spotted monitor, freshwater crocodiles, northern blue-tongue lizard and northern quolls) to recognise and avoid the taste of cane toads. It’s called taste aversion training, and it’s a bit like getting food poisoning at a restaurant and never going back there (CTC, 2019).

By dropping cane toad sausages and very small cane toads (known as ‘metamorphs’) into vital habitats, native predators are exposed to a small amount of toxin that makes them sick but doesn’t kill them. When they later see and smell a larger adult toad, they’ll know to avoid it. It’s already been trialled with great success in one area of the Kimberley, and they need your help to expand the project (CTC, 2019). For further information please see HERE.

The Australian White Ibis is a common sight in many Australian towns and cities and is often referred to as a ‘bin chicken’ because of its varied diet (Vincent, 2022).

Despite their reputation, ibis birds are actually helping Australia with one particular issue… cane toads.

These underrated birds are a key player in the evolution of Australia’s native species to coexist with and control the invasive cane toad (Vincent, 2022).

CANE TOAD AND THE IBIS

When cane toads are threatened by predators, they excrete toxin from the paratoid glands on the back of their neck to poison their attacker and if they are stressed enough, they will empty the glands through this process.

Ibis have learned to use the cane toads’ own defence strategy against them. Ibis will pick up cane toads and fling them about, causing them to become stressed and expel all their toxin. The birds then rinse the toads off in water, or wipe them in the wet grass to remove the poison, before swallowing them whole!

It’s very encouraging to see that native animals are learning how to cope with cane toads. One day, we are confident that native animals will be able to manage cane toads on their own. Until then, we still need to give them a helping hand through toad busting activities (Vincent, 2022).

The ‘stress and wash’ method of eating cane toads has also recently been observed in Cattle egrets, Purple swamphens and Moorhens. This is a learned behaviour and it’s been observed in multiple different regions. It is hoped that it will have an impact, especially as more species tag along and copy the behaviour (Vincent, 2022).

Professor Shine said “the introduction of invasive species often leads to a population boom followed by a decline in numbers. One of the reasons that happens is the native species work out how to deal with them. We have lots of rodents, that’s the native rats and house rats, that can eat cane toads. It’s absolutely true that the system comes back into some kind of a balance and we have native predators getting to exploit this new food source” (Vincent, 2022).

CANE TOAD AND DOMESTIC DOGS

Toad toxicity occurs when an animal ‘mouths’ a cane toad. Often our furry friends can’t resist chasing cane toads as they hop across the yard, and with their slow hop they are more often than not caught. However, once caught the cane toad’s defensive mechanise kicks in – they release their deadly toxin. The cane toad secretes its venom through glands which are located at the back of their head. The cane toad’s venom is very sticky and irritating, but also poisonous. Be sure you know the signs and symptoms of toad poisoning in dogs as it could save their life (AES, 2022a).

Symptoms of toad toxicity in pets

There are many signs and symptoms of cane toad poisoning in dogs. These signs and symptoms vary in their severity, but the longer your pet is exposed to the toxin the worse their symptoms will become.

These signs and symptoms can include:

- Drooling or foaming at the mouth

- Red and slimy gums

- Pawing at mouth

- Vomiting

- Disorientation

- Dilated pupils

- Increased heart rate

- Panting or difficulty breathing

- Wobbly gait or loss of coordination

- Muscle twitches and tremors

- Part of body (legs) or whole-body going rigid

- Seizures

- High body temperature

- Death

For a more in-depth look into the signs and symptoms of cane toad poisoning, visit our Toad Toxicity blog (AES, 2022b).

What to do if your pet has mouthed a cane toad

If you see your pet with a toad, you should immediately wipe the gums with a damp cloth, continually rinsing the cloth in-between wipes. This will need to be done for at least 10-20mins. For a step by step guide on how to remove the toxin from your pet’s mouth, visit our What to do if Your Pet Licks a Toad blog.

Do not direct a hose into your pets mouth. This may force water into the lungs (AES, 2022a).

How to prevent toad toxicity in pets

Toads are a nocturnal menace. They regularly poison dogs, such as Terriers, which often chase small animals. To prevent the problem, do not allow your dog to go outside unattended at night. Take it out on a lead if the need arises. Place two or three bells on your dog’s collar. The bells will not affect the toad, but you will learn to recognise the tell-tale jingling sound the bells make when your dog is ‘suspiciously active’. Immediate investigation when the bells are ringing may save your dog’s life (AES, 2022a).

There are several ways to control the toad population in your yard, including:

- Place wire mesh (6mm x 6mm) around the outside of your fence. The mesh should be buried 10cm and extend at least 40cm above the ground

- Try to trap the toads with funnel traps along the fence, or by placing a very deep bucket in the ground near a light – the toad is attracted to the light, falls into the bucket, and can’t climb out

- Eliminate, as much as possible, any fresh standing water as the toads look for fish-free water in which to breed

- Cover swimming pools and turn out pool and outside lights as much as possible

If you believe your pet has come in contact with a cane toad, contact your closest Animal Emergency Service hospital or your local vet immediately.

FURTHER INFORMATION

- Where are cane toads found

- How to identify a cane toad

- Are all toads poisonous to dogs?

- Are dead cane toads still poisonous?

- How does poisoning occur?

- What are the signs of cane toad poisoning?

- How long does cane toad poisoning take to kill a dog?

- How do I treat cane toad poisoning in my dog?

- How is cane toad poisoning treated by vets?

- Can I prevent my dog from coming into contact with cane toads?

- What to do if you have cane toads on your property

How to Identify

Many people can’t tell the difference between a native frog and a cane toad because they share features such as warty skin, a visible ear drum and webbed toes (DPE, 2023).

However, unlike native frogs, adult cane toads have all of these features:

- distinct bony ridges above the eyes, which run down the snout

- a large parotoid gland behind each eye

- unwebbed hands but webbed toes

- dry warty skin

- cane toads can range in colour from grey, yellowish, red-brown, or olive-brown, with varying patterns (DPE, 2023).

Some species of native frogs are easy to mistake for a cane toad. Before you kill a cane toad, make absolutely sure it is a cane toad.

Native frogs play an important part in our environment and are protected in NSW by the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016.

Listen to the calls of some native frogs that are sometimes mistaken for cane toads and read the guide Friendly frog or invasive cane toad? to help you identify the invasive cane toad pests (DPE, 2023).

Staying Safe

Despite popular urban legend that licking cane toads can get you high, this is purely a myth. However, humans can get incredibly ill if the toxin is ingested and if sprayed with it can cause intense pain, temporary blindness and inflammation. If this is what it can do to humans, then it can definitely kill dogs, other household pets and native animals (CTC, 2019).

Where can they be found?

References

Animal Emergency Service (AESa), 2022. Symptoms of Cane Toad Poisoning in Dogs (Toad Toxicity). https://animalemergencyservice.com.au/blog/symptoms-of-cane-toad-poisoning-in-dogs.

Animal Emergency Service (AES,b), 2022. Cane Toads and Dogs (everything you need to know about toad poisoning). https://animalemergencyservice.com.au/blog/cane-toads-and-dogs/.

The Cane Toad Coalition (CTC), 2019, 10 facts about cane toads, WWF-Australia,

https://wwf.org.au/blogs/10-facts-about-cane-toads/.

The Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (DCCEEW), 2023, The cane toad (Bufo marinus) – fact sheet. Commonwealth of Australia.

https://www.dcceew.gov.au/environment/invasive-species/publications/factsheet-cane-toad-bufo-marinus

– (DCCEEW, 2023)

Department of Planning and Environment (DPE), 2023, How to Identify a cane toad, NSW Government,

Vincent, E, 2022. Ibis use ‘stress and wash’ technique to eat poisonous cane toads. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-11-23/ibis-find-way-to-eat-toxic-cane-toads/101683596.