Location

Cairns: People, Hazards (Crocodiles) and History

People - Cairns Traditional Owners

I would like to acknowledge the Traditional Custodians on the land on which I was living and exploring and pay my respects to the pay my respects to the Elders past and present. I extend that respect to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who live there today.

Traditional Custodians within the Cairns region include:

- the Djabugay;

- Yirriganydji;

- Bulwai and Gimuy Walubara Yidinji;

- Bundabarra and Wadjanbarra Yidinji;

- Mandingalbay Yidinji;

- Gunggandji;

- Dulabed and Malanbara Yidinji;

- Wanyurr Majay;

- Mamu and Ngadjonjii peoples (Cairns City Council, 2023).

If you would like to know more about the traditional owners and/or their customs and culture, please visit:

- Queensland Government – First Nations culture

- The National Museum of Australia – Community stories

- Cairns Regional Council – Proud Indigenous cultures with a long history and bright future

- Wet Tropics – Local Cultural Connections

- Tourism Tropical North Queensland – Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Culture.

-

Hazards - Crocodiles

Cairns is Croc country. For safety’s sake, you must assume that anywhere with water in far north Queensland will have a crocodile.

The crocodiles in the region are saltwater crocodiles (estuarine crocodiles); they can live in freshwater but prefer saltwater and the foods found there.

Where – from the Boyne River south of Gladstone, Croc country goes right up the East coast of Queensland and across to the Northern Territory border.

Crocodiles can travel hundreds of kilometres inland and have been found not only in oceans, rivers and creeks but also in swamps, waterholes and dams.

What to do to be safe:

First and foremost – Have common sense.

Secondly – have respect for the animal and its home.

Stay 5m away from the water’s edge; this will not eliminate the risk, but rather minimise the risk. Crocodiles like to hunt and ambush their prey. Staying 5 metres away from the water’s edge allows you an opportunity to get away should one lunge at you. They do not tend to chase prey after the lunge, but it is always safer to move away should it happen.

A crocodile can lunge out of the water at speed, and they are able to launch their bodies vertically up out of the water.

They are able to run on land, but in water is where they excel, and they can swim at up to 40km per hour.

When camping near the water edge in FNQ, camp at least 50 metres away from the high tide water edge.

Do not leave meat or other food out next to your campsite. Do not put fish scraps or old bait at boat ramps, as this can put the next people visiting the location at risk.

They are most active at dawn and dusk and can stay underwater for over an hour.

At night, you can shine a torch into the water and see their bright red eyes watching you.

Keep pets away from the water’s edge and ensure dogs are always kept on a leash.

Breeding season is from September to April.

If you want more information about crocodiles and being safe in Queensland, the Queensland Government have a Crocwise page.

Crocwise videos

To read more about Crocodiles, please visit our Crocodile page.

History of Cairns

Prior to Cairns settlement:

Original inhabitants

The Aboriginal population is believed to have entered Australia at least 40,000 years ago. Current opinion favours migration through various parts of northern Australia, including the Cape York Peninsula. Traditional local Aboriginal stories recall hunting and fishing on land that once extended past Green Island during a time of lower sea levels. Archaeological evidence shows Aboriginal peoples living in rainforests in the Cairns area for at least 5,100 years and possibly for much of the often suggested 40,000-year period.

The first recorded human occupants of the Cairns area were Australian Aboriginal peoples. Tribal groups speaking the Gimuy Walubara Yidinji language were generally on the south side of the Barron River. On the northern side, particularly in the coastal area from the Barron to Port Douglas, Yirrganydji groups generally spoke dialects of the Djabugay language.

James Cook

On 10 June 1770, English maritime explorer Lieutenant James Cook visited and gave a European name to the inlet. In his journal, he commented, “The shore between Cape Grafton and Cape Tribulation forms a large but not very deep bay which I named Trinity Bay after the day – Trinity Sunday – on which it was discovered.”

Phillip Parker King

Lieutenant Phillip Parker King, one of the most important early charters of Australia’s coast, made three marine surveying expeditions to northern Australia in 1819, 1820, and 1821. All three expeditions included visits to Fitzroy Island, located about 22 kilometres (14 mi) from Cairns. On King’s first visit, he drew attention to the availability of drinking water and the presence of Aboriginal people in the area.

Owen Stanley

In June 1848, Captain Owen Stanley undertook a ten-day hydrographic depth sounding survey of the Trinity Bay region. His consequent official map listed “Native Huts” at present-day Palm Cove, and “Many Natives” and “Native Village” on the stretch of coast immediately north. Green Island was marked “Low Bushes”, and the future site of Cairns was indicated as “Shoal” and “Mangroves”.

Settlement: Assessment of site

The first historical event of significance leading up to the establishment of Cairns was an essay published in a Sydney newspaper in 1866. The article, by J. S. V. Mein, a ship commander appointed to set up a bêche-de-mer plant at Green Island, helped increase southern awareness of the northern location. In 1872, William Hann led a prospecting expedition in the Palmer River, where an extensive gold field was located. The announcement of this location in September 1873 by James Venture Mulligan resulted in an influx of prospectors, which became the basis for the first large non-indigenous populations to inhabit Far North Queensland.

In 1873, the extensive and detailed reports of the George Dalrymple exploration party indicated the assets and potential of Trinity Inlet:

The excellent anchorage and watering place appear to have been used some years since as a beech de mer fishing station and to be now a place of frequent call by vessels of that trade and passing ships. I believe very little engineering difficulty will be encountered in forming the necessary wharves on deep water, and from the appearance of the ranges, I do not anticipate any difficulty in obtaining a passable road over them to the interior.

Dalrymple also noted the number of Aboriginal groups in the area: “Many blacks were seen round the shores of the bay. Blacks campfires burn brightly during the night in glens of the mountainsides.”

In March 1876, three years after the Palmer River discovery, James Mulligan announced that an even more extensive gold field had been found at the Hodgkinson River on the Atherton Tableland, 122 kilometres (76 mi) west of Trinity Inlet. This site was of sufficient size to warrant serious consideration of the building of a track to the coast and the establishment of a coastal wharf and settlement to export the mineral. Sub-Inspector Alexander Douglas led a party to cut an access track in three days, from the tableland to the coast through 32 kilometres (20 mi) of thick lawyer vine scrub. The track was completed on 23 September 1876 and was later named the Douglas Track.

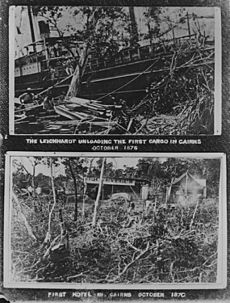

Official settlement:

The first government officials arrived by boat and pitched their tents opposite the site of the present-day Pacific International Hotel. On 7 October 1876, the Governor of Queensland, William Wellington Cairns, proclaimed a new northern port at Trinity Bay. On 1 November 1876, the township was inaugurated at a luncheon given by Captain T. A. Lake on board the Government ship SS Victoria. This is regarded as the official birth date of Cairns. The first public land sales in February 1877 were supplemented three months later by the construction of the first local sawmill, making use of the abundant natural timber resources.

Early development:

Cairns’ growth was spurred by Chinese agricultural ventures, overcoming competition from Port Douglas and Smithfield. The 1886 railway to Herberton brought Italian and Irish immigrants, fueling agricultural demand and boosting Cairns’ importance. The 1887 railway to Myola led to the development of Kuranda. A. J. Draper, a prominent mayor, championed community interests, while Reverend Ernest Gribble worked to protect Aboriginal rights, leading to the establishment of the Yarrabah mission. The late 19th century saw significant agricultural growth, the construction of the Mulgrave tramway, the establishment of a natural gas supply, and the gazettal of Barron Falls as a national park, solidifying Cairns’ position as a regional centre.

Cairns township

Cairns was declared a town in 1903, with R. A. Johnstone’s memoirs, “Spinifex and Wattle,” providing valuable insights into local Aboriginal culture. The establishment of a harbour board in 1906 spurred architectural growth, leading to the construction of numerous heritage-listed buildings. The Cairns Post began publication in 1909, followed by the opening of a vital water supply and a new district hospital in 1911 and 1912, respectively. The early 20th century also witnessed the development of Malay Town, marking the arrival of the area’s first significant migrant community.

Cairns city

Post-WWI development:

Cairns experienced labour and goods shortages during WWI, followed by a period of quiet growth. In 1923, it achieved city status. Significant developments in the 1920s included the opening of the Daradgee Bridge, the introduction of public electricity, and the establishment of Cairns High School.

Cyclone Willis devastated the city in 1927. The 1930s saw the introduction of the cane toad, a disastrous ecological event, alongside the development of hydroelectricity and the establishment of the first commercial radio station, 4CA.

The 1939 cyclone caused significant flooding, altering the course of the Barron River.

World War II

World War II spurred the construction of the Kuranda Range Road as an emergency evacuation route. Cairns served as a key Allied base during the war, leading to a mass evacuation of residents in 1942. Post-war, the Australian Army conducted extensive anti-malaria research, significantly improving the understanding and control of tropical diseases.

Post-WWII recovery

Following WWII, a series of ex-army equipment auctions boosted the local economy. The 1947 HMAS Warrnambool incident highlighted the ongoing danger of mines. In 1949, Mayor Collins was defeated after 22 years in office. Increased accessibility came with the arrival of Trans Australia Airlines and the establishment of ABC 4QY radio.

The 1950s saw the opening of the Amberglow cannery and Calvary Hospital, while the city celebrated its 75th anniversary with the “Back to Cairns” celebrations. Harbour dredging resumed, and the city continued to recover from the war.

Cultural expansion

The 1950s saw significant tourism growth in Cairns. The 1953 release of Bob Bolton’s promotional film “There’s A Future For You in Far North Queensland” and the arrival of the Sunlander train boosted tourist numbers. Queen Elizabeth II’s 1954 visit further enhanced the city’s international profile.

Other key developments included the expansion of the water supply, the arrival of Italian migrants, the construction of a new railway station, and the impact of Cyclone Agnes. The 1956 Olympic torch relay and the filming of “Cinerama South Seas” further boosted the city’s image.

Infrastructure improvements

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Cairns witnessed significant infrastructure development. The city embarked on a major sewering project, the Cairns Historical Society was formed, and a tourist area was declared.

Key developments included the establishment of a cyclone-warning radar station, the commissioning of the Barron Gorge Hydroelectric Power Station, and the opening of a bulk sugar terminal, all of which contributed to the city’s growth and economic development.

Continued growth

The 1960s and 1970s saw significant developments in Cairns. The release of “The North Queensland Annual” and the arrival of television boosted tourism. The establishment of “The Northerner” and the publication of Trezise’s book on Quinkan art increased cultural awareness.

The city witnessed technological advancements with the acquisition of a mainframe computer and the development of the Barron Gorge Hydroelectric Power Station. The hippie commune movement emerged, and the city experienced social and cultural shifts with the opening of Rusty’s Markets and the establishment of HMAS Cairns.

The 1970s also saw the construction of crucial infrastructure, including the sewering of the city, the development of a new water supply, and the construction of modern bridges. The city celebrated its centenary, and significant cultural institutions like the Cairns Civic Center and the Cairns Public Library were established.

Modernisation

The 1980s saw the rise of high-rise development in Cairns, though a proposed casino development was met with strong opposition. The construction of the Kuranda Range Road and the opening of Cairns International Airport significantly improved accessibility. The establishment of Tjapukai Dance Theatre and the World Heritage listing of the Wet Tropics rainforest boosted tourism.

The 1990s witnessed significant infrastructure development, including the construction of Skyrail, the amalgamation of local councils, and the opening of Cairns Central Shopping Centre. The city also experienced social and cultural growth with the establishment of the Cairns Convention Centre, the Reef Festival, and the Tjapukai Cultural Park.

Key events of this period include the successful opposition to the proposed casino development, the controversial construction of the Cape Tribulation Road, and the significant cultural impact of the Olympic torch relay.

21st century Cairns

The 2000s saw the inauguration of the Cairns Festival and the opening of a new public swimming lagoon. The Cairns Convention Centre achieved global recognition, and significant legal victories were won by the Djabugay and Mandingalbay Yidinji people in their native title claims.

The withdrawal of Daikyo from North Queensland in 2005 marked the end of a major era of Japanese tourism investment. Dr. Timothy Bottoms’ comprehensive history of Cairns, “Cairns City of the South Pacific,” was published in 2015.

Reference: